About Lab

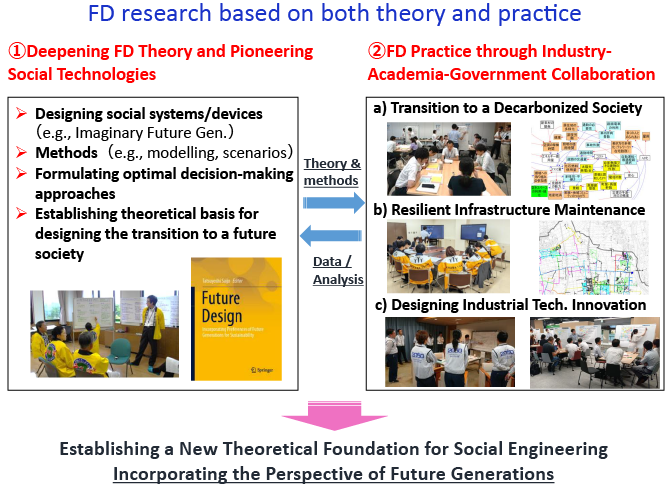

Characteristics of Research

Our laboratory has pioneered both theoretical research and social practices related to Future Design. As shown in the figure below, our laboratory's defining characteristic is conducting research activities based on two complementary pillars: deepening theoretical research on Future Design (left side) and practices aimed at solving real-world societal challenges (right side). Through this approach, we are advancing the design of societal systems and mechanisms to ensure a sustainable society for future generations and pioneering a new form of social engineering that incorporates temporal dimensions, such as the preferences of future generations.

Another defining feature of our Future Design practice is its collaboration with diverse stakeholders, including government agencies, local governments, industry, and research institutions. The scope of Future Design practices spans multiple domains, including but not limited to resources and energy, carbon neutrality, environmental planning, urban planning and community development, educational program development, and industrial

Research Activities at Graduate Level

【Example of Master’s Program】

During the spring and summer semesters of the first year of the master's program, students learn about cutting-edge discussions and practices in Future Design through seminar/research meeting in the laboratory, where they take turns presenting and discussing relevant papers. During the same semester, the Graduate School of Engineering at the University of Osaka also offers a lecture course titled “Future Design” (15 class periods, 2 credits), allowing students to deepen their understanding and concepts related to Future Design. Additionally, the theme for their master's research is solidified during this period.

Full-scale research activities commence in the fall/winter semester of the first year. Our laboratory emphasizes Future Design practices through collaboration with stakeholders such as public institutions (e.g., local governments) and industry. Students can advance their research within these collaborative frameworks. This enables them to pursue cutting-edge Future Design research while gaining a tangible sense of how the laboratory's research activities connect to real-world decision-making and solving actual challenges.

Depending on the research theme, students will also acquire the necessary methodologies and skills (such as data analysis and modeling) for that specific research and apply them to their work.

Messages from Graduates

Class of 2023 Graduate

In collaboration with the Suita City Waterworks Department in Osaka Prefecture, we researched how introducing "Imaginary Future Generations (IFGs)" changes perspectives on water infrastructure maintenance and management. This was achieved through a large-scale questionnaire survey and deliberation workshops involving city employees.

②What did you learn through your research activities and Future Design studies?

Through Future Design research, I learned both the difficulty and necessity of appropriately incorporating the perspective of “future generations”—something people living in the present often struggle to consciously consider—into evaluations in advance. Regardless of whether it's work or personal life, I've noticed that in various choices, factors like future outlook and sustainability are increasingly being integrated into evaluation criteria, and the weight given to these elements as evaluation factors has grown significantly. Furthermore, through the large-scale questionnaire survey and discussion practice conducted in collaboration with Suita City's Waterworks Department, I learned the importance of mindset and hypothesis when working with numerous stakeholders.

③How are the lessons learned in your laboratory and research activities being applied now? Also, please share a message for the future development of Future Design.

Future Design research can contribute to societal development by evaluating future potential across all domains and making appropriate judgments. Working in the risk management department of a financial institution, I recognize that risk assessments are required not only in traditional fields but across diverse sectors. I believe the Future Design approach will prove valuable when making appropriate risk-taking and risk-hedging decisions in these new domains, even when lacking prior expertise.

Class of 2024 Graduate

In collaboration with internal and external stakeholders, I conducted comparative analysis and verification of discourse content between Imaginary Future Generations (IFGs) and the present generation. This involved analyzing speech data from two Future Design workshops using “text mining (key terms, co-occurrence networks, etc.)” and “third-party evaluation.” Through this process, I extracted characteristics of IFGs' discussions and thought processes and examined the usefulness of the evaluation methodology.

②What did you learn through your research activities and Future Design studies?

Through studying Future Design, I gained a process and mindset that involves temporarily setting aside the interests of the present generation to evaluate matters from the perspective of future generations. In my master's research, I learned the importance of capturing issues from multiple angles by visualizing the discourse of both present and future generations, clarifying evaluation criteria, and iterating between qualitative and quantitative assessments.

③How are the lessons learned in your laboratory and research activities being applied now? Also, please share a message for the future development of Future Design.

I've developed the habit of pausing to consider whether this decision will be the right one for people ten or twenty years from now. I believe that simply sharing this perspective in corporate or community discussions can lead to calmer consensus and less biased choices. Moving forward, I aim to expand this mindset into the “methodology” of meetings and workshops, embedding long-term oriented decision-making into our daily systems

Class of 2025 Graduates ➊

In collaboration with Suita City and Toyonaka City in Osaka Prefecture, Nishinomiya City and Amagasaki City in Hyogo Prefecture, the Kinki Bureau of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, and the Kinki Regional Environment Bureau of the Ministry of the Environment, we conducted workshops to study the effectiveness of introducing Imaginary Future Generations (IFGs) in examining and building consensus on integrated measures for disaster prevention and carbon neutrality.

②What did you learn through your research activities and Future Design studies?

Through my master's research activities, I believe I have acquired research execution skills commensurate with a master's degree and developed the skills necessary for working professionals with graduate degrees after graduation. Specifically, through weekly seminars focused on learning about Future Design, I gained the ability to independently set research questions addressing unresolved aspects of Future Design, investigate prior research, formulate hypotheses, and conceptualize the research process.

Furthermore, through progress reports in the seminar and presentations at academic conferences, I developed the ability to clearly communicate research content and engage in logical discussion.

Additionally, studying Future Design (FD), the core theme of this laboratory, allowed me to learn about environmental issues, societal challenges, and the perspectives and approaches held by individuals, local governments, and businesses. This experience enabled me to acquire broad knowledge and perspectives that span multiple fields, extending beyond my undergraduate major and specialized knowledge.

③How are the lessons learned in your laboratory and research activities being applied now? Also, please share a message for the future development of Future Design.

I believe FD research is the only research theme that, in addition to cultivating the research execution skills required for master's programs, allows students to learn how entities such as local governments, national governments, and corporations engage with society and address sustainability issues from their perspectives, and to understand how people's thinking changes through the lens of IFGs. Therefore, through FD research, I believe science and engineering undergraduates can gain exposure to entities they would otherwise have no contact with. This exposure allows them to acquire diverse perspectives and ways of thinking from various entities—perspectives that would likely have been lacking as science and engineering professionals after graduation—and apply them in their future careers.

Furthermore, FD is a relatively new field of study, and there are many aspects regarding its introduction into society and its effects that still need to be clarified. In other words, it is no exaggeration to say that the further development of FD depends on the FD research conducted by each and every student in the Hara Laboratory. I sincerely hope that as many students as possible in the Hara Laboratory will take an interest in and engage with FD research.

Class of 2025 Graduates ➋

In collaboration with Mito City, Ibaraki Prefecture, and Ibaraki University, I conducted a study to verify the effectiveness of implementing Future Design in climate change adaptation issues.

②What did you learn through your research activities and Future Design studies?

The high degree of freedom in research allowed me to independently identify and tackle challenges. Furthermore, conducting the Future Design practice in the administrative field broadened my perspective.

③How are the lessons learned in your laboratory and research activities being applied now? Also, please share a message for the future development of Future Design.

I currently work at an IT company, but I feel that my perspective has expanded beyond just technology to include how we should disseminate it to society over the long term. I believe the evolution of technology will continue to accelerate, and I think Future Design will make a significant contribution in the process of implementing it within society.

Class of 2025 Graduates ➌

In collaboration with Yahaba Town, Iwate Prefecture, we verified the effectiveness of introducing Future Design for evaluating the Urban Master Plan through workshops, questionnaire surveys, and other methods.

②What did you learn through your research activities and Future Design studies?

Through this research, I have come to realize that by adopting the perspective of Imaginary Future Generations (IFGs), we can gain insights and perspectives that cannot be obtained by simply considering the future from the present viewpoint.

③How are the lessons learned in your laboratory and research activities being applied now? Also, please share a message for the future development of Future Design.

We hope that as initiatives like Yahaba Town's take on Future Design as an organizational effort spread nationwide, awareness of Future Design will further increase, accelerating research across various fields.

Messages from Future Design Practitioners

Mr. Rituji Yoshioka, Manager, Yahaba town, Iwate Prefecture

In Yahaba Town, we developed a method called “multi-layered resident participation” for our waterworks business, working with residents to envision the future of our water supply. Workshops became forums for serious discussions about what we could do now for the future, with proposals like “We should raise water rates to prepare for the future.” However, we felt these discussions inevitably remained within the “acceptable range based on current constraints,” making it difficult to sufficiently broaden long-term challenges and future options. It was then that The University of Osaka proposed Future Design (FD). Yahaba Town has applied this approach to formulating its “Regional Revitalization Plan,” “Waterworks Business Management Strategy,” “Comprehensive Management Plan for Public Facilities,” and “Comprehensive Plan.” We have come to realize that taking the perspective of future generations significantly changes the quality of the discussion. Many participants commented, “Thinking about the town's future makes current challenges clearer,” and these insights are reflected in policy direction.

②Please share your outlook for future Future Design practices.

Yahaba Town has been incorporating Future Design (FD) into policy-making in collaboration with the Hara Laboratory at The University of Osaka. In 2023, we applied it for the first time to an “assessment” of an administrative plan, conducting a workshop involving 20 staff members using the Urban Master Plan as the subject. Participants were divided into the current generation and Imaginary Future Generations (IFGs). After four rounds of discussions, they combined both perspectives to propose five key policy measures. Particularly for challenging issues like “the gap between urban development and rural areas,” considering the perspective of future generations enabled a reassessment of potential risks and values, leading to realistic and sustainable improvement measures. This initiative reaffirmed that incorporating the viewpoint of future generations can bring into sharp focus challenges that are difficult to see through the lens of the present alone.

Yawata Town intends to utilize FD, including assessments, not only for urban planning but also for evaluating the future of infrastructure supporting daily life, such as water supply and sewage systems.

Mr. Naoki Kusumoto, Manager, Suita City, Osaka Prefecture

Suita City has long collaborated with Osaka University on surveys and research in areas such as the environment, based on a partnership agreement. In fiscal year 2014, the research team at Osaka University proposed a new initiative involving Future Design. As part of this survey and research, the city held its first Future Design workshop inviting citizens.

Since then, the themes of Future Design practice have expanded from environmental issues to waterworks and community development. Participation has also broadened to include other municipalities, resulting in numerous workshops.

The Future Design workshops have proven effective. Participants assume the role of Imaginary Future Generations (IFGs), shifting their perspectives beyond their current positions and experiences. This fosters diverse idea generation and invigorates communication. It encourages participants to consider the future 30 years from now as their own concern, enabling them to adopt a bird's-eye view that balances the interests of both the current and future generations. Consequently, many distinctive ideas emerge that transcend the status quo, emphasizing the need for new systems and the associated mindset shifts. Furthermore, at the conclusion of each workshop, participants report a sense of unity, expressing sentiments like “I wish we could continue a little longer” or “It was enjoyable.”

We anticipate that expanding the circle of Future Design will facilitate smoother information sharing and collaboration with other organizations when implementing various initiatives, leading to the effective advancement of measures.

②Please share your outlook for future Future Design practices.

During the formulation of our city's Third Basic Environmental Plan, we conducted a citizen-participatory Future Design workshop. While scheduling and preparation for implementation presented challenges, we believe this framework proved highly effective for examining long-term issues such as environmental problem-solving.

We intend to continue expanding the use of Future Design—both as staff training to enhance administrative skills and as a mechanism to effectively incorporate citizen voices into policies during the next plan revision.

Why not consider various issues and visions as future generations yourselves?

Mr. Masahiro Eguchi, Manager, Organo Corporation

As an initiative to create new businesses addressing future societal challenges, we collaborated with the Osaka University team (Hara Laboratory) from fiscal years 2019 to 2021 to conduct workshops utilizing Future Design (FD) for generating mid-to-long-term R&D themes. Through this FD practice, we experienced how it generates new ideas distinct from those stemming from current extensions. We believe that cultivating a perspective that surveys the future holds universal value—applicable not only to setting R&D themes but also to corporate long-term strategies and, ultimately, decision-making in our daily lives.

②Please share your outlook for future Future Design practices.

We aim to apply Future Design (FD) approach to addressing urgent societal challenges related to sustainability—such as climate change, water resources, ecosystems, and resource circulation—which require a long-term future perspective. Through FD, we seek to invigorate communication with diverse individuals both inside and outside the company, promote new talent exchanges, and co-create future-oriented ideas.

Kansai Bureau of Economy, Trade and Industry (Person in charge)

Ministry of the Environment Kinki Regional Environment Office

(Person in charge)

We first implemented Future Design at the Kinki Regional Committees on Energy Supply and Demand and Prevention of Global Warming held in December 2023, primarily with the following three objectives:

・ To invigorate discussions and make the conference more meaningful

・ To strengthen relationships among conference participants through active discussion

・ To foster new collaborative initiatives among participants through strengthened relationships

As the “Future Design Practice,” we conducted a workshop adopting Future Design methodologies centered on the theme: “Initiatives to be realized within the next decade to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.” The Committee is unique in the Kinki region, bringing together diverse stakeholders involved in energy and climate change countermeasures, including national government agencies, local governments, industrial support organizations, and private companies. The workshop facilitated lively discussions. While we have not yet heard of new collaborative initiatives emerging, we felt significant progress in invigorating discussions and strengthening participant relationships.

Furthermore, in 2024, we established the “Future Design Subcommittee for Achieving Carbon Neutrality.” This subcommittee centered its theme on carbon neutrality and conducted workshops adopting the Future Design approach. The outcomes of these discussions have been compiled and published as the “Idea Catalog for Achieving Carbon Neutrality by 2050.”

②Please share your outlook for future Future Design practices.

Our Future Design practice has yielded three major benefits. First, it enables us to adopt a long-term perspective and work backward from our 2050 goal to achieve carbon neutrality. Second, it allows us to think freely as Imaginary Future Generations (IFGs) , detached from our current organizational affiliations or positions. Third, it allows for incorporating diverse perspectives and ideas, leveraging diversity. These benefits were reaffirmed as highly applicable when considering solutions to administrative challenges, community development, and corporate management strategies.

Particularly in addressing global warming, it is essential that all stakeholders recognize their respective roles and collaborate to advance initiatives. This collaboration generates synergistic effects that surpass the combined efforts and impacts achievable by any single stakeholder acting alone. We anticipate that through the increased adoption of Future Design, such synergistic effects will emerge nationwide, ultimately accelerating progress toward achieving carbon neutrality.

Career Paths of Graduates

【Further Education】Graduate School of Economics, The University of Osaka

【Employment】Kansai Electric Power Co., Inc., Kintetsu Group Holdings Co.,Ltd., SoftBank Corp., Fujitsu Limited, IBM Japan Systems Engineering Co., Ltd., Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation